Laura Earnshaw, one of the volunteers at Tameside Archives and Local Studies, has investigated a tragic and shocking story of death, damage and destruction in Ashton during World War One. It highlights the dangers of the new developments in weapons and warfare for those who worked in munitions and those who lived nearby. We are familiar with the damage done by enemy bombs during World War 2, but this must have been all the more devastating for being so unexpected.

Ashton Munitions Explosion, Wednesday 13th June, 1917

There is a story in my family that my Great-Great Aunt was seated in the dentists’ waiting room, and as she got up and went through the door to the surgery, the waiting room blew in! Beyond this family legend, I had not heard of the Ashton Munitions Explosion until a few weeks ago; this is something I truly appreciate about this blog; that local histories and stories are now finding a new audience! I have predominantly researched the event from The Ashton Munitions Explosion 1917 written by amateur historians, John Billings and David Copland, and held at Tameside Local Studies and Archive Centre. I also looked at the original news stories, as reported in the Ashton Reporter (dates 16/06/17; 23/06/17; 30/06/17; 07/07/17; 14/07/17; 28/07/17), though these were mainly ‘shock’ stories of the horrific injuries of the dead and wounded, and the destruction caused by the explosion.

Illustration: A drawing of the layout of Hooley Hill Mill, The Ashton Munitions Explosion 1917

What Happened?

The Hooley Hill Munitions factory was located on William Street, in the Portland Place Ward of Ashton-under-Lyne, next to the canal. The Ward was the site of several mills and businesses, and around 2000 houses.

On the afternoon of Wednesday 13th June, Chief Chemist and co-founder of the Hooley Hill Rubber and Chemical Company, Sylvain Dreyfus, was in the nitrating house with chemist Nathan Daniels, when the mixture in nitrator No.9 began leaking, catching fire as it fell on the wooden staging surrounding it. Fellow chemist Frank Slater immediately attempted to roll the barrels of T.N.T out of the building to avoid an explosion, but he succumbed to the fumes and collapsed; lab assistant John Morton raised the alarm, and removed Slater’s collapsed body, as the factory set alight, detonating 5 tons of T.N.T .

The Hooley Hill Rubber and Chemical Company opened in March 1915 by Sylvain Dreyfus and Lucien Gaisman. Originally contracted to produce 10 tons of T.N.T a week, by 1916 they delivered 22.5 tons weekly, as need grew. Billings and Copland suggest that the entrenchment and machinery of the First World War meant that high explosives were needed in greater volume than ever before. The State could not produce enough ammunition with its existing factories, so, with the formation of a new Ministry of Munitions in 1915, with greater powers, it could increase private contracts to produce the T.N.T required for the increased munitions, explosives and artillery used. Indeed, 76 million tons was produced in 1917, compared to the half a million tons produced by Britain in 1914. One such contract was won by Dreyfus and Gaisman in 1915, for their new factory in Ashton-under-Lyne.

Illustration: Plot of the damage wrought by the explosion, made on 1909 map of Ashton-under-Lyne.

Horrific Damage

46 people were killed by the explosion on the 13th June 1917, as the nitrating house set on fire, detonating 5 tons of T.N.T and igniting two gasometers in flames. 120 people were hospitalised, with another 300-400 more with minor injuries caused mainly by the windows shattered in the surrounding mills.

The Hooley Hill Mill itself was obliterated, the waste acid tanks blown into the canal.

Railway workers on the adjacent line were killed outright, and the tracks themselves bent. Of the school children playing nearby, who had come to see the explosion, eleven died from injury.

The glass windows in the surrounding mills blew in, injuring workers inside; windows in shops in King Street in Dukinfield were also reported as shattered. Clayton’s Mill caught fire, and Bridge End Mill collapsed. Houses were peppered with debris: approximately 100 were demolished, though the Ashton Reporter stated that Spring Grove Terrace “caught the full force” (16/06/1917).

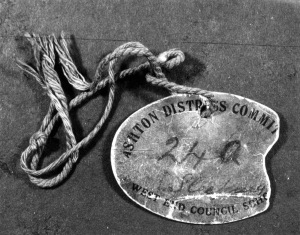

‘Sleeping in’ tag for Cecilia Pathson, who slept at West End School when her house was damaged

‘Sleeping in’ tag for Cecilia Pathson, who slept at West End School when her house was damaged

The sewage works were also damaged, and the gas works were eventually shut, due to pipe damage.

Of the men near the nitrating house, John Morton survived, as did Frank Slater, though he was burnt in the explosion. Unfortunately, Nathan Daniels died four days later, from burns sustained: Dreyfus was cut in two by the explosion, and only identified by his initials in his clothing.

The Ashton Relief Fund

Paper handkerchief to commemorate the Ashton Explosion 13th June 1917

Paper handkerchief to commemorate the Ashton Explosion 13th June 1917

It is difficult to convey the full extent of the devastation wrought by the explosion – The Ashton Reporter described the area as “square mile of desolation” (16/06/17). The Mill had blown up at around 4.30pm on 13th June. By the evening, Ashton Town Council had created three sub-committees to deal with the after-effects of the tragedy, overseeing the burials of those killed, and the feeding and housing of the homeless, of which there were approximately 2000. Mayor Alderman Heap had also founded the Ashton Relief Fund to raise money to compensate those affected, until such a time as the insurance money could be paid. Indeed Lord Beaverbrook gave the first £500 – he had been sent by the government as a “representative to assist in the provision of state compensation”. As Max Aitken however, he had been elected as MP for the Ashton Unionist Party constituency, and served until his peerage in 1916. To raise money for the Fund, poems were sold and charity concerts and Cricket matches put on. George Formby Sr. even performed at the Theatre Royal on the 30th June, and held an auction afterwards. By August 1917 £10,000 had been raised to feed, accommodate and be distributed to those affected: when the Fund was closed in June 1919, £11,700 had been given in support to those wounded or families left without a home or breadwinner by the explosion, until the Government could arrange compensation. The Government had previously covered the cost of Third Party claims at the Silverton Munitions Explosion in January 1917, an incident which killed 69 people. On the 25th June the Ministry of Munitions announced that it would pay third party claims at the Ashton Munitions Explosion and an office was set up at Clarence Arcade, Stamford Street.

The public funerals for those killed were held on Sunday 17th June. The corteges were stationed in front of the Town Hall, with the flags at half mast. The horse drawn funeral and mourning carriages were accompanied to the cemetery by the Town officials, Council members, clergy, and the bands of the Manchester Regiment and Salvation Army, with crowds of around 250,000 people following behind with mounted police. The families only, attended the funerals at Dukinfield Cemetery, while 10,000 “sightseers”, paid 3d to the Ashton Relief Fund in order to see the remains of the factory site.

The mass funeral held for the victims

Inquest and Inquiry

A Government investigation into the cause of the explosion was undertaken by Dr. Edward Edgar, “government scientist and inspector”. Sylvain Dreyfus had been experimenting with a new technique of creating T.N.T before the explosion, though he had kept the details secret until he could determine if it would work. Though the report did confirm that this new method of production did increase instability, it must be remembered that the Government at the time had no powers to determine how T.N.T was produced by its private suppliers, and was only entitled to monthly inspections of new munitions factories while they were under construction, or if they were behind in production. It must also be remembered however that the proprietors of the Hooley Hill Mill did take safety precautions. The Mill had fireproofing measures, the wooden decking surrounding the nitrators was an acknowledged danger, and, with the increased production of T.N.T by the factory, steps had been taken to remedy this. Labour and materials were scarce, however, and though Dreyfus had prioritised it, the Ministry of Munitions did not issue ‘priority certificates’ as the replacement of woodwork was not “absolutely necessary”, only desirable. Work was thus slow. Following the investigation, a Secret Report was produced on the 16th August 1917, the conclusions of which agreed with the verdict of the public inquest on the 12th July, a month previously. The conclusion of ‘Accidental Death’ after the nitrating pan boiled over, causing a fire and explosion was reached by both the Inquiry and the Public Inquests (Sylvain Dreyfus, death certificate, Billings and Copland, Notes, pg 46). The site of the Hooley Hill Rubber and Chemical Company was put up for auction on 9th December 1918, with the remaining T.N.T sent to Wales for destruction.

The Ashton Reporter (30/06/17) printed letters from soldiers serving abroad responding to news of the munitions explosion in Ashton-under-Lyne, including responses from ‘former Ashtonians’ living in Canada. The outpouring of grief and the support offered to those who had lost loved ones, homes or jobs was phenomenal in this tragedy in Ashton’s wartime history.

I’m pleased you found this interesting. I undertook a project with St. Peters School in 2007. I wrote a book called Names on the Wall to share the information I had researched with parents at the archives. The music teacher at the school developed a song cycle and the drama teacher from the then Stamford High worked with the children to develop a drama. The children performed for the mayor and other dignitaries on the 9th anniversary. The money raised by sales of the book and cd’s of the song cycle with funding from the council and the EU allowed a commemorative statue to be unveiled the following year by the Tameside Magistrates court. A new performance is being prepared to be performed on the 100th anniversary this year. The whole of the story I wrote can be read on my website.

Elaine Schofield

My great uncle was Richard Roberts one of the school children killed whilst walking home from school holding his brother, Charles’ hand. Charles survived.

Why on earth would you think this could have been done deliberately? And, who would have done it? The workers worked hard and needed their jobs, the principal of the company was right there with them. The fact that he was Jewish and most of the workers presumably Christian would have little impact on the actual work and its danger.